What to watch for

After completing this lesson, you’ll be able to:

- Summarize the progression from early forms of communication and media to telecommunication and mass media

Now that we have our feet under us with some (very) introductory thoughts about the evolution of human communication and early media, it’s time to move ahead quickly to the development of telecommunication and then to mass media.

Telecommunication—literally communication across / at a distance—in a sense goes back as far as shouting, but we’ll take a more fine-grained look at things here.

Required Reading:

History of telecommunication

Mixed in with my notes on this required reading are bits and pieces about early forms of mass media (media designed to communicate to many people simultaneously), too. Read the article first, then come and read this section, maybe with the article still open in another browser tab.

Early telecommunication (smoke signals, drums, horns, etc.)

Each of these early methods of communicating over a distance (not to mention many others not listed here) is a fascinating topic of study in its own right, worthy of further study. For the purposes of this class, though, we’ll have to move quickly, noting just that they were all innovative solutions to communicating over a distance. Also, they all faced the limitation of being real-time only—a common constraint for many forms of telecommunication.

Greek semaphore (and other optical telegraphs)

These early telecommunications systems are so cool—you absolutely should go read more about Greek hydraulic semaphore systems, in particular.

Each of these systems was adapted to the specific needs of the culture that designed it, and in general, they offered a higher degree of precision than earlier systems. Some even incorporated rudimentary encryption.

They all shared several downsides, though: they required a fairly substantial investment in terms of construction and operation, and because they were optically based, they were limited to line-of-sight communication—even poor weather could limit their efficacy1.

Couriers / mail

Couriers (and more formalized mail systems) allowed for written communication to be shared over a distance.

When these systems worked, they were a major innovation—people could finally precisely communicate with others over any distance traversable by humans (or pigeons—seriously!). However, these systems faced many potential pitfalls: letters could be lost or intercepted, they required a high degree of trust in the messenger, and—significantly—they required knowledge on the part of the sender and the courier of where to deliver the message.

Early newspapers

Although newspapers really took off after the invention of the printing press, early newspapers arrived along with the advent of couriers and mail, taking the form of gazettes and bulletins—pieces of writing specifically designed to be read and / or displayed publicly.

In many ways, these early newspapers were the first form of mass communication. Unsurprisingly to anyone familiar with current forms of mass media, they were soon used to advertise and for propaganda.

Still, they were a big deal: they were a big step up from news spreading by word of mouth—everyone (at least in a specific locale) could get the exact same information (trustworthy or not) simultaneously.

Printing press with moveable type

It’s hard to overstate just what a big deal the moveable type printing press was. Take a look at one in action:

(Video via Kottke—worth watching by clicking through from interesting bit to interesting bit)

Though still obviously a time-and-labor-intensive process 2, the printing press was a true revolution, ushering in the era of mass media. It offered an improvement of several orders of magnitude in terms of the speed and the cost of producing copies of written works.

As we’ll see time and time again in this course, price is absolutely a core component of technological advances. The larger social effects of a new technology often arrive only once it goes from a niche technology affordable only by the wealthy—which books were, before the printing press—to something the common person can afford.

The pace at which the printing press enabled knowledge and ideas to spread directly affected every aspect of human culture.3

Typewriter

I mention the typewriter after the printing press because doing so represents a useful, common pattern: new technological and social revolutions often occur when large—in terms of size / cost / complexity—forms of media are made available to individuals, usually by greatly reducing one of those three factors.

If this were a more focused course, we’d have a wonderful time camping out on the topic of the typewriter for a good long while.

Telegraph (+ telephone, radio, and television)

Another huge deal: the first form of electronic telecommunication. Its biggest innovation: speed. The telegraph was the first technology that reproduced one of the key aspects of face-to-face human communication: (effectively) real-time transmission of information.

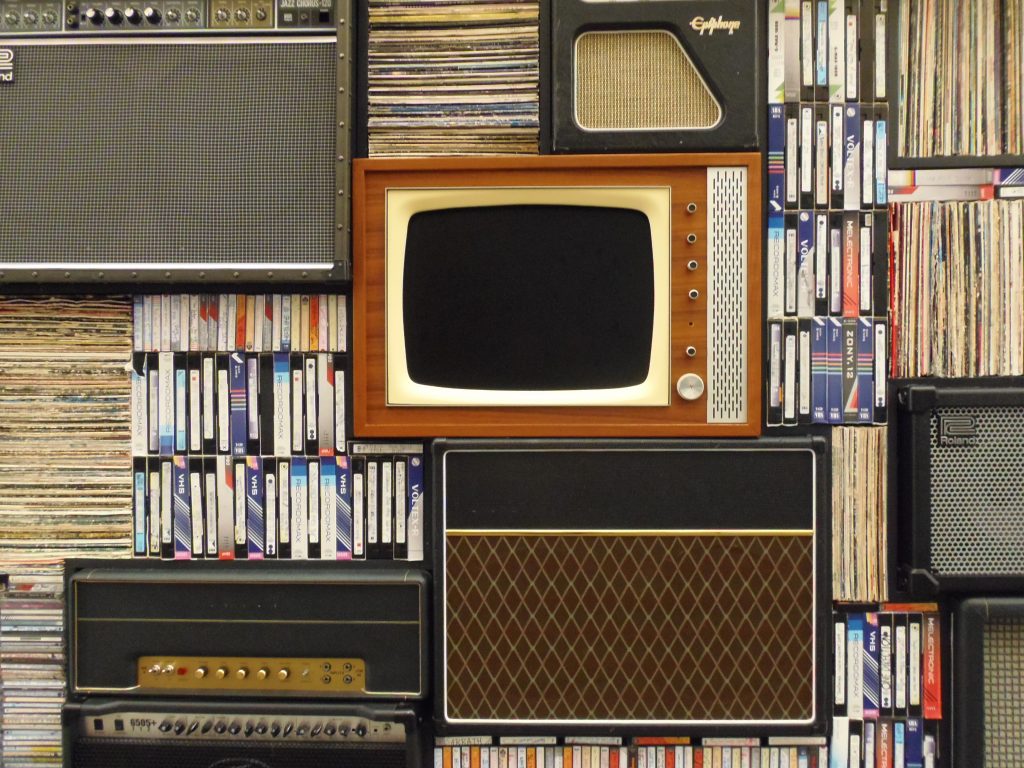

In many ways, every form of telecommunication after the telegraph just represented layering in another information stream to the telegraph. The telephone brought one-to-one, bi-directional real-time audio (and radio one-to-many real-time, one-way audio), and television one-to-many real-time video.

So much else to say about the telegraph:

- It offers our first chance to talk about Metcalfe’s law 4: “the value of a telecommunications network is proportional to the square of the number of connected users of the system.” That is, the value of a network scales exponentially, not linearly, with each additional person that uses it. Think deeply about this law—it’s vitally important.5

- Telecommunications technologies often require massive investments in infrastructure.

- The telegraph also reveals another truth about disruptive technologies: they’re often far worse than existing technologies on many vectors (for the telegraph: lacking the warmth and nuance of face-to-face human interaction, required lots of infrastructure / expensive equipment, had to learn a new language, less room for expression (in many ways) than books), but far far far superior on one key vector (for the telegraph: speed). Successive iterations of the technology then keep the key innovation and gradually layer back on all the stuff that was “missing” as compared to previous forms of communication (see: the telephone, television, etc., all the way up to FaceTime, Periscope, etc.).

Again, if this were a different course with a different focus, we’d spend far, far more time on each of these new forms of media. They’re each fascinating and deserving in their own right, but we’re supremely focused on the macro view.

Computers and computer networks

The innovations brought about by computers and, especially, computer networks will be the focus of the remainder of the course. Since that’s the case, I want to begin with one essential thought.

It’s so easy to view the most recent developments in human history as superlative: the best, the most important, etc. While I think there’s a non-zero chance of the digital revolution representing an essential turning point on human history, we impoverish our thinking if we fail to adequately account for just how innovative and important past technologies and forms of media truly were.

Since we’re about to dive deep on many of the specific innovations brought about by the digital revolution, I’ll simply list two of the most essential macro-level ones here before we conclude this lesson:

- The ability to perfectly reproduce information ad infinitum at a cost that over time has become asymptotically close to zero.

- The ability to store and process information at a scale and speed beyond human ability.

Now, on to the building blocks of new media: hardware, software, and networks.

Non-required readings

what3words

Related to the development of couriers and postal systems, an innovative effort to make all places on Earth easily addressable.

“What Was the Greatest Era for Innovation? A Brief Guided Tour” by Neil Irwin

An especially fun read in light of this lesson.

Episode 156: “Yo, Dingus”, The Talk Show (Podcast audio link)

Though directly talking about voice assistants and AI (and maybe I’ll include this reading in that lesson, too), the conversation here about how humans get and adopt new technologies is so very spot-on. (Please pardon the profanity in the sponsor read.)

Discussion Questions

- Imagine being able to communicate with people at a distance only via primitive methods of communication. What would the challenges be? Perhaps more interestingly, what could be fun about them, or how could people show personality or express their humanity with them?

- You should probably talk for a minute about how cool the Greek semaphore systems were.

- Try and think of examples that you know from history or literature where the unreliability of the mail / couriers influenced events.

- Spend some time thinking / talking about a) from a current perspective, what a royal pain the Gutenberg printing press was and b) from a historical perspective, how amazing it was compared to everything that came before it. Then, carry out the same exercise with methods of communication of your choice.

- The telegraph was a big deal. Talk about whatever interests you about it for a bit.

- Look up your current / home address on what3words.

- Argue about which era was the greatest for innovation.

- Talk about the segment on the podcast included in the non-required readings. Do you agree with the pattern it outlines?

Words on / reading time for this page: 1,599 words / 8-12 minutes

Words in / reading time for required readings: 3,053 words / 15-20 minutes

Total words in / reading time for this lesson: 4,652 words / 23-32 minutes

Insert complaint about satellite TV in poor weather here.↩

Just think about this video next time your printer acts up!↩

See: the Enlightenment, etc., etc., etc.↩

Although I suppose languages themselves could count in a sense?↩

No, seriously: stop reading right now for at least sixty seconds and think about it. I’m not kidding.↩